Coexisting with AI in the era of Education 4.0

The question of how much AI should be allowed in education, particularly at the university level, has become a hot topic of debate within the global education community.

Lack of clear regulations

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into education has garnered significant public and media interest. Whether and how AI should be appropriately utilized remain contentious issues, with diverse opinions leading to varied practices worldwide.

While programs like the International Baccalaureate (IB) permit limited AI usage for assignments and dissertations, many countries express concerns about students overly relying on AI tools. Consequently, over 30,000 schools globally employ AI detection tools such as Turnitin, ZeroGPT, WinstonAI, and Copyleaks to identify AI-generated work and impose penalties. However, the effectiveness of these tools remains a matter of debate.

Research by Associate Professor Mike Perkins, Head of the Centre for Research and Innovation (CRI) at British University Vietnam (BUV), reveals that while AI detection tools flagged 91% of submissions as AI-generated, only 54.8% were accurately identified, and 54.5% were reported for academic misconduct. These findings underscore the challenges of detecting advanced AI-generated content and interpreting AI detector results effectively.

In Vietnam, AI tools like ChatGPT remain in a "grey area" as most universities lack specific regulations for their use in learning and research. Although institutions acknowledge AI's potential to support students, concerns linger over the reliability of verification methods and the development of fair monitoring mechanisms.

Reliability of AI detection tools

Evidence suggests that AI detection tools are not foolproof and can be bypassed with simple techniques, raising fairness concerns. For instance, ZeroGPT demonstrated a high error rate for Vietnamese content.

A study published in the International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education—a top-tier journal—conducted by Perkins and BUV students Vu Hai Binh and Khuat Quang Huy, revealed that AI detection tools were only 39.5% accurate for unedited AI-generated content, dropping to 22.1% after minor user edits.

Perkins emphasized the ease with which these tools can be manipulated through simple techniques, such as introducing errors to make AI-generated content appear more human-like. He stressed the need for caution when relying on these tools for academic verification, especially given AI's rapid advancement.

Empowering control

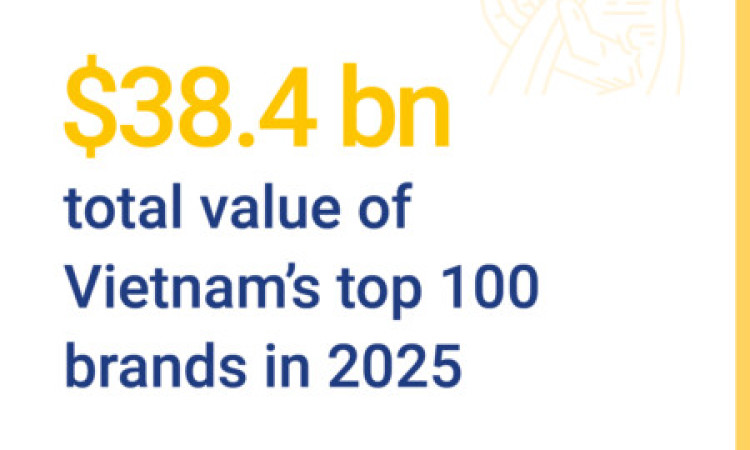

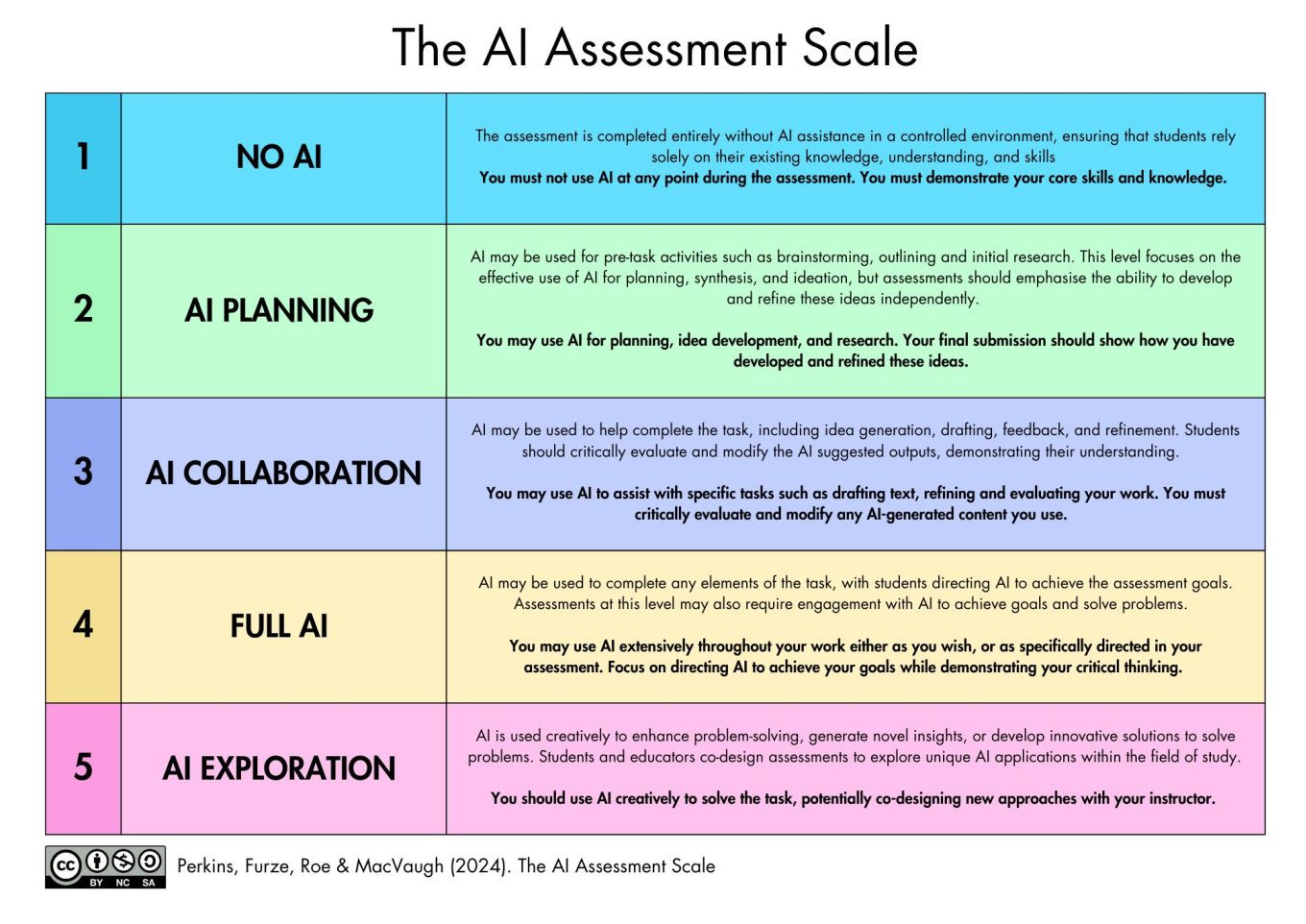

To address these challenges, Perkins recommends using the AI Assessment Scale (AIAS), a comprehensive framework developed by him and his colleagues. The AIAS features five levels of AI usage, from "No AI usage" to "AI Collaboration," enabling students to use AI tools within defined parameters.

Lecturers can adjust the permissible level of AI usage based on subject requirements. Pilot results indicate that the AIAS significantly reduces AI-related cheating and shifts educators' focus from policing AI usage to guiding ethical and responsible use.

The AIAS framework is globally recognized, translated into 13 languages, and implemented in countries like the USA, UK, Australia, and Malaysia. It has been featured at UNESCO Digital Learning Week, QS Higher Ed Summit Asia Pacific and won the Best Paper Award for 2024 in the Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice.

In Vietnam, BUV is leading the application of the AIAS, helping students understand AI's scope in their work and simplifying lecturers' evaluation processes. Its success at BUV demonstrates that AI can be integrated into education effectively. Encouraging students to "coexist" with AI, rather than prohibiting it, aligns with the ethos of the 4.0 technology era.

When used ethically and under guidance, AI tools can enhance students' learning experiences, making them valuable allies in modern education.